Beyond Kimwolf: How Residential Proxy Networks Enable Enterprise Lateral Movement

Residential proxy networks enable direct access into internal enterprise environments, enabling attackers to bypass perimeter defenses and perform lateral movement from within trusted networks at massive scale.

--

Editor’s Note — Jan 28, 2026

Spur contributed to recent Google Threat Intelligence research on disrupting the largest known residential proxy network. The findings published by Google reflect the same residential proxy behaviors and risks explored in this post, with our analysis focused specifically on lateral movement and internal network exposure.

--

Residential Proxies and the Hidden Risk of Lateral Movement Inside Enterprise Networks

Residential proxy networks are typically discussed in the context of fraud, scraping, or account abuse. Increasingly, however, they represent a more serious and less understood risk: unauthenticated access to internal networks at massive scale.

In this post, we break down what we’ve observed while analyzing residential proxy infrastructure, why recent disclosures (including Kimwolf) only scratch the surface, and what SOC teams should understand about the lateral movement and internal exposure risks created by these networks.

Background: Residential Proxies Are Not New, But New Uses Are Emerging

We’ve been tracking residential proxy infrastructure since 2019, starting with early commercial providers and explicitly criminal services. While branding and operators have changed over time, the core model remains the same:

- A proxy SDK or service is embedded into consumer devices (e.g., mobile phones, streaming boxes, apps).

- That device’s IP and connectivity are resold as part of a proxy network.

- Customers can egress traffic from real residential or mobile endpoints.

Historically, the primary concern was external abuse, like fraud, credential stuffing, scraping, or evasion of IP-based controls. What was assumed – but rarely tested – was whether these proxies could be abused in the opposite direction, into the networks they reside within.

We decided to test that assumption.

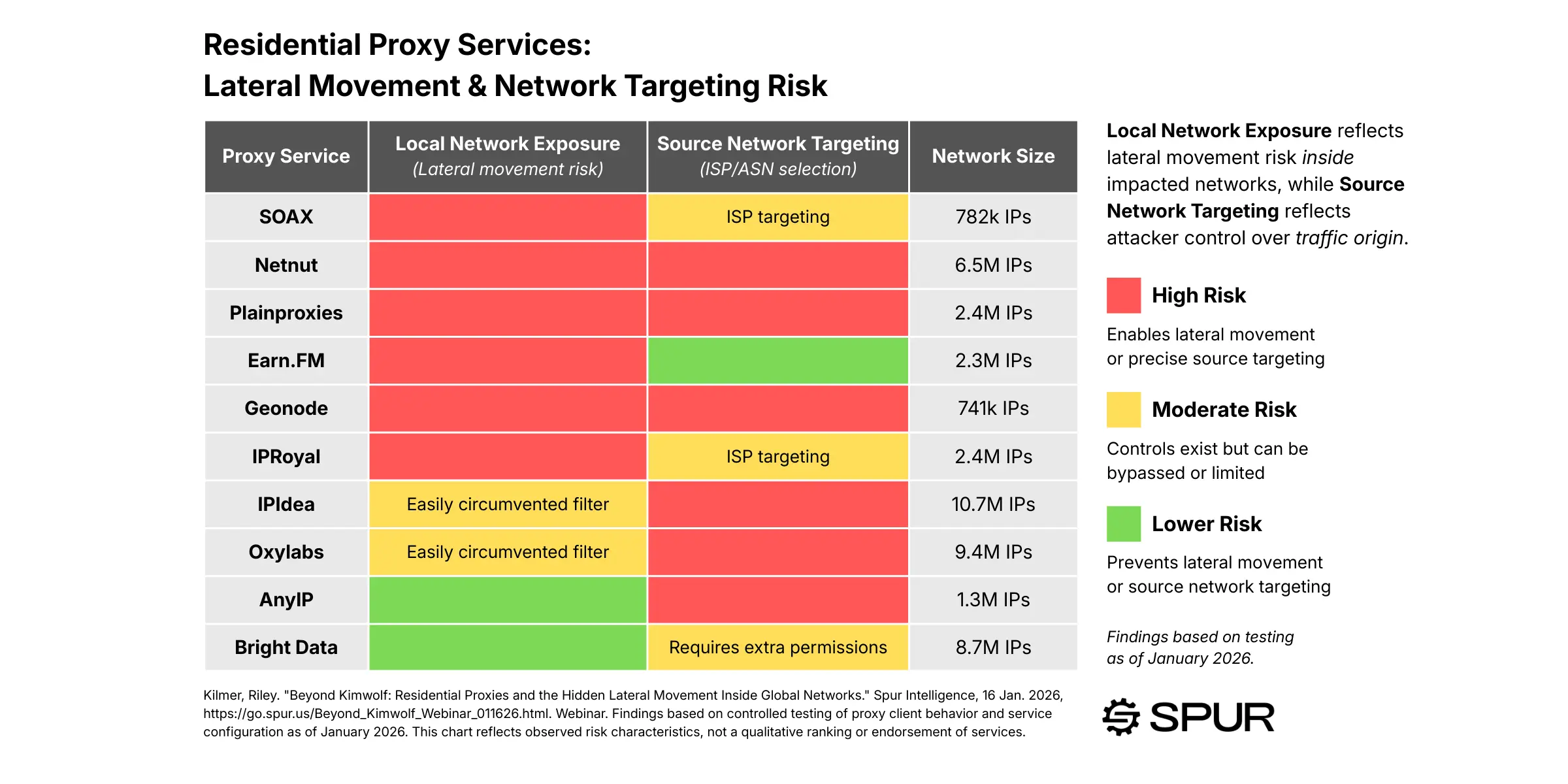

The Core Finding: Local Network Access Is Widely Allowed

Across nearly every residential proxy service we tested, local network access was permitted by default. This means a proxy customer could:

- Route traffic through a compromised device.

- Resolve or target RFC1918 address space (e.g., 10.0.0.0/8, 192.168.0.0/16).

- Directly access resources on the same local network as the proxy endpoint.

Only a small minority of providers implemented meaningful safeguards. In most cases:

- There was no blocking of private IP ranges.

- There was no validation at the proxy layer.

- Filtering, when present, was superficial and easily bypassed via DNS resolution behavior.

The implication is straightforward: Residential proxies can be used as internal footholds, not just anonymous external infrastructure.

Why This Matters to SOC Teams

Many security architectures implicitly trust internal network boundaries. Devices inside a network – especially those behind NAT or assumed to be “consumer-grade” – often receive far less scrutiny than internet-facing systems.

Residential proxy abuse breaks that assumption. If a proxy endpoint exists inside a corporate office, utility network, defense contractor, financial institution, or a telecom or ISP ASN then the proxy operator or customer can pivot internally with no phishing, no malware delivery, and no perimeter breach.

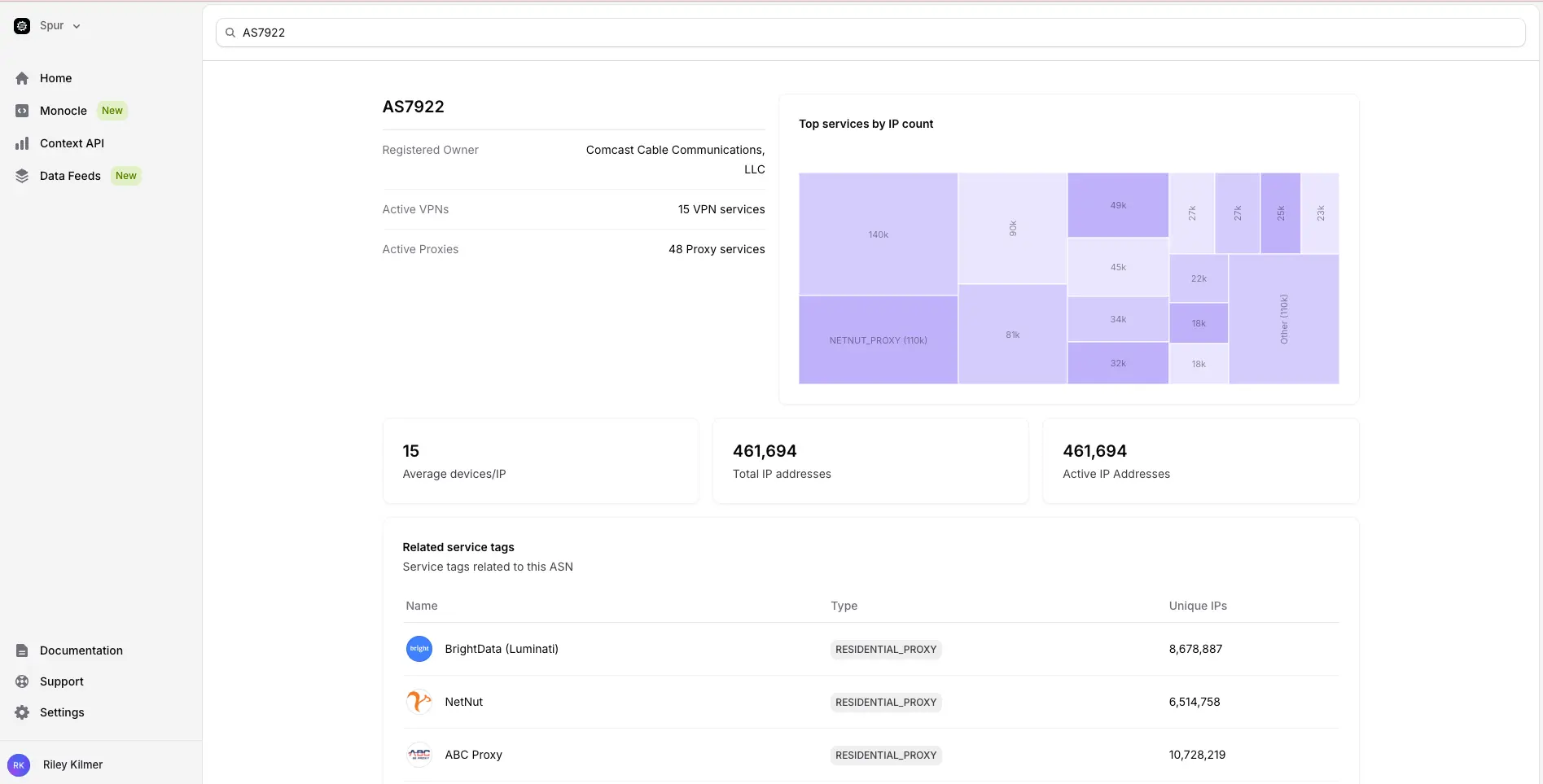

ASN Targeting Turns This Into a Scalable Threat

Most modern residential proxy services allow customers to select exit nodes by country, city, ISP, or ASN. ASN targeting is particularly concerning. An attacker does not need to know a specific IP address. They can:

- Identify an ASN associated with a target organization.

- Select that ASN in the proxy service.

- Iterate across proxy endpoints until landing inside the desired environment.

- Begin discovery and lateral movement from within.

This is no longer theoretical. We observed hundreds of enterprise and critical infrastructure ASNs hosting active residential proxy endpoints.

Ephemeral Devices, Persistent Exposure

One argument often raised is that these devices are transient, for example mobile phones, laptops, or consumer hardware that move between networks. But this actually makes the problem worse. Residential proxy networks are highly ephemeral, constantly cycling across home networks, offices, cafés, hotels, and enterprise environments. A single proxy network may expose millions of IPs in a day and tens of millions over a 90-day window.

From a SOC perspective, this means exposure is unpredictable; indicators age out quickly; and traditional blocklists or static IP-based controls are insufficient.

Kimwolf Was a Symptom, Not the Disease

Recent reporting from Krebs on Security and investigations by Comcast highlighted the Kimwolf operation, which used residential proxy infrastructure to access locally exposed services on consumer devices and deploy malware. While important, this case represents only one exploitation path. It focused on a specific device class, relied on a known service exposed locally, and resulted in a secondary botnet.

The broader issue is more fundamental: The proxy layer itself allows local network access.

Even if individual vulnerabilities are patched, the architectural risk remains as long as:

- SDKs allow LAN access

- Proxy services do not enforce RFC1918 restrictions

- Internal networks trust device locality

Internal Discovery Is Trivial Once Inside

Once a proxy endpoint is inside a network, exploitation becomes a standard internal discovery problem:

- Network scanning

- Service enumeration

- Credential reuse

- Misconfigured admin panels

- Internal APIs

- IoT and OT devices with weak or no authentication

This does not require advanced tooling. Off-the-shelf scanners and frameworks are sufficient.

For SOC teams, this means the initial access vector may never appear in perimeter logs, because it never crosses the perimeter.

What We Observed in Real Networks

When analyzing ASNs where residential proxies were present, we identified exposure across the following industries:

- 318 Utility companies

- 298 Government owned/operated ASNs

- 166 Healthcare companies/hospitals

- 141 Banking & Finance institutions

- 14 Aerospace companies

In many cases, we cannot determine how networks are segmented internally. Segmentation may mitigate impact, but it cannot be assumed.

If a compromised device can access internal DNS, management interfaces, flat VLANs, or legacy systems, then the proxy can too.

Why “Front-End Fixes” Are Not Enough

Some proxy providers have attempted to mitigate this by:

- Blocking private IP ranges at request time

- Pre-resolving DNS responses

- Implementing basic filtering rules

But these measures are fragile.

We observed multiple cases where:

- DNS caching behavior allowed bypass

- Resolution tricks defeated filters

- Proxy software itself still permitted the connection

The only durable mitigation is enforcing restrictions at the SDK or proxy core, not at the UI or API layer.

Unfortunately, many of these SDKs are embedded in firmware, consumer devices, or third-party apps that are unlikely to be patched comprehensively.

What to Do Next & Implications for Detection and Response

This threat model changes several assumptions:

- “Internal” does not mean trusted.

- Residential IPs can be internal.

- Proxy traffic may represent lateral movement, not ingress.

Practical steps include:

- Monitoring for known residential proxy indicators inside corporate ASNs.

- Treating unexpected proxy traffic as a potential internal foothold.

- Separating BYOD from any corporate resources and having good device segregation policies in place.

- Removing apps, games, cheap Android TVs containing residential proxies from your home networks. (Check https://spur.us/context/me to see if one is on your local network.)

- Disallow corporate devices from installing untrusted browser extensions/apps.

- Avoiding unauthenticated internal services wherever possible.

Residential proxy networks have evolved beyond a fraud-enablement problem. They now represent a structural security risk that blurs the line between external and internal threats. Not that every proxy endpoint equals compromise, but the attack surface now exists where many teams are not looking.

Understanding where residential proxies appear in your environment is the first step toward reducing that risk.

How Spur Can Help

Spur helps security and threat hunting teams identify and contextualize residential proxy exposure inside their environments by providing high-fidelity, infrastructure-level visibility into proxy networks operating across the internet and within enterprise ASNs.

We continuously detect and classify residential proxy services, including those embedded in mobile and consumer devices, and surface where they appear at the ASN and IP level. This enables security teams to determine whether proxy activity is occurring inside their own address space, not just targeting their external assets.

Beyond simple labeling, Spur provides additional context, such as observed device counts and churn behavior, that helps analysts assess whether proxy traffic is likely originating from a single compromised endpoint or a large, shared carrier network. This enables more precise alerting, reduces false positives, and supports informed response decisions rather than blanket blocking.

For SOC teams focused on internal threat detection, Spur’s data can be used to:

- Identify residential proxy services present within corporate or subsidiary ASNs.

- Prioritize investigation of low-device-count proxy endpoints that may represent internal footholds.

- Validate segmentation assumptions and monitor exposure over time.

- Integrate proxy intelligence into existing detection, SIEM, and response workflows.

As residential proxies continue to blur the boundary between external infrastructure and internal access, Spur provides the visibility needed to understand where that boundary has already been crossed.

For more on how Spur powers better IP decisions, including helping security and fraud teams stay ahead of what’s next, contact us for a strategy briefing. To experience our high-fidelity IP intelligence in action, sign up for a free trial today.

Also, check out the webinar where we examined this vulnerability in detail.

See the Difference Between Raw Data & Real Intelligence

Start enriching IPs with Spur to reveal the residential proxies, VPNs, and bots hiding in plain sight.