It’s a scary world out there for residential IPs; they are the key product of “underground” proxy services like Faceless, SocksEscort, NSocks, the defunct 911 Proxy, and now CloudRouter which we suspect has taken its place. But productization of residential IPs is not limited to scary dark web storefronts. There are a surprising number of legitimate “bandwidth sharing” applications enticing users to sub-lease their Internet connection for mere pennies per gigabyte, and an even more surprising number of users who are fine with this exchange. We’ve talked about the market for residential IPs ad nauseum, but it feels like the problem is only getting worse.

A modest proposal

Picture this scenario: you’re out on the town and are approached by a man in a nice suit with a spiffy briefcase (which is surely full of important papers and not crackers). Exuding confidence and professionalism, he makes you an interesting offer. He happens to know the bartender at your favorite pub and says you can put a couple of free beers on his tab whenever you’re in town. In exchange, he asks for the permission to use your phone to make a series of calls for his business endeavors. He assures you that all such calls will be completely legal, adhering to a stringent set of ethical standards he personally oversees. Additionally, he might occasionally allow a handful of his trusted business partners to use your phone number for their calls, also bound by the same rigorous guidelines.

Now, another scenario: Imagine you’re walking down an empty street when a shadowy figure steps out from an alleyway, dressed in trench coat and with a mysterious shadow cast over his face, like the cliché antagonist from an old film noir flick. He subtly grabs your attention and makes you different offer. He presents you with a state-of-the-art smartphone, loaded with every app and feature you’ve ever wanted, no subscription fees, no one-time payments—completely free. But there’s a catch.

In exchange for this dream device, the shadowy figure asks for the permission to use your new phone to make any calls he wants, anytime, without needing to inform you. He assures you that you won’t even notice, that it’ll be as if the calls never happened. But there’s more—he also wants the freedom to let anyone he chooses use your phone number to make their calls, again without your direct knowledge.

This analogy attempts to illustrate the surface-level difference between explicit bandwidth sharing apps (like EarnApp, Honeygain, Pawns, Repocket, Cash Raven, Pop, etc) and the countless “free VPN” apps like MaskVPN. The end result is mostly the same, but at least with the former you’ve got a vague idea of what your phone is being used for while you enjoy your “free” beer.

Bright Data (EarnApp) and Oxylabs (Honeygain) pay their peers the most—which is not much—and generally make an attempt to enforce KYC policies on their customers. To be clear, this is not an endorsement. The bar is just really low. Either way, your IP address, once a personal line to the world, can now be used in dealings you’re unaware of, for purposes unknown to you, and by people you’ve never met.

If you’re a reader of this blog, the dodgy nature of bandwidth sharing offers probably doesn’t need explaining. You’re not here to be told off for downloading and running questionable software that blatantly plans to monetize your IP address. But a significant portion of residential proxies stem from people who apparently see no problem with this exchange.

Will the real 911 Proxy, please stand up?

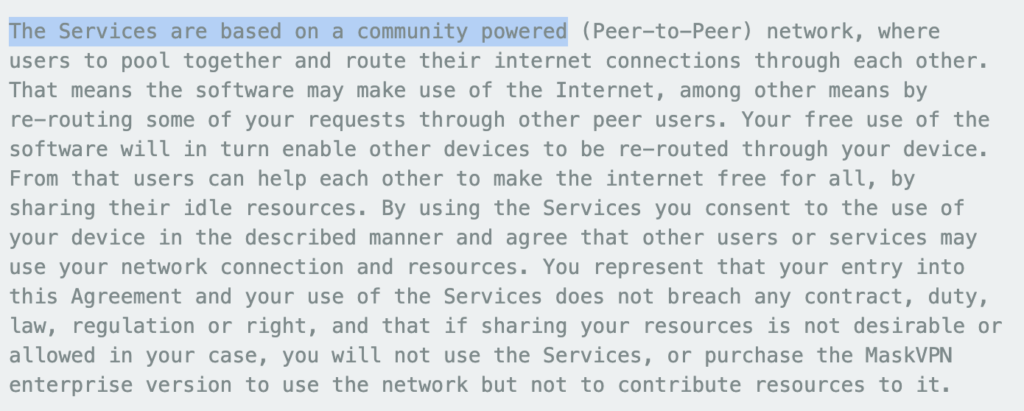

One such example was MaskVPN, whose users unknowingly contributed to the pool of IPs for the criminal proxy service 911.re aka 911 Proxy—a service that went belly-up in the fall of 2022. Unsurprisingly, MaskVPN also disappeared shortly thereafter. Since then, the void left in the market has had a lot of attempted fillers, some we’ve written about in the past. Do a Google search for “911 proxy” and you’ll find dozens of services claiming to be the best replacement. This seems like a dubious accolade for most commercial proxy services who at least pretend to be on the level; 911 proxies (and thus MaskVPN users) were consistently responsible for large scale banking fraud and corporate ATO operations.

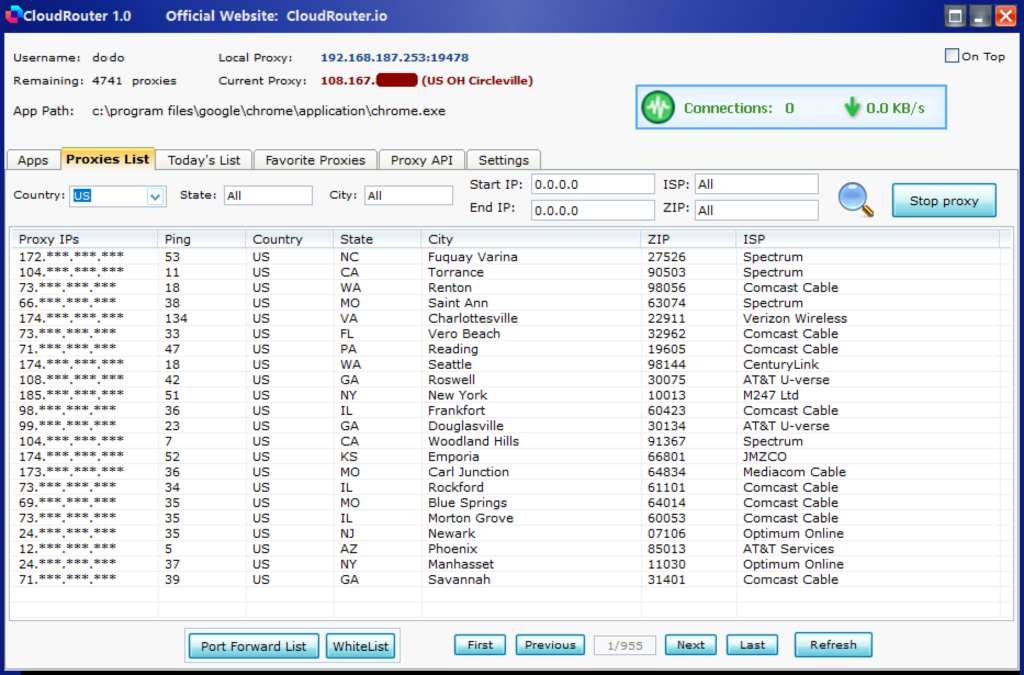

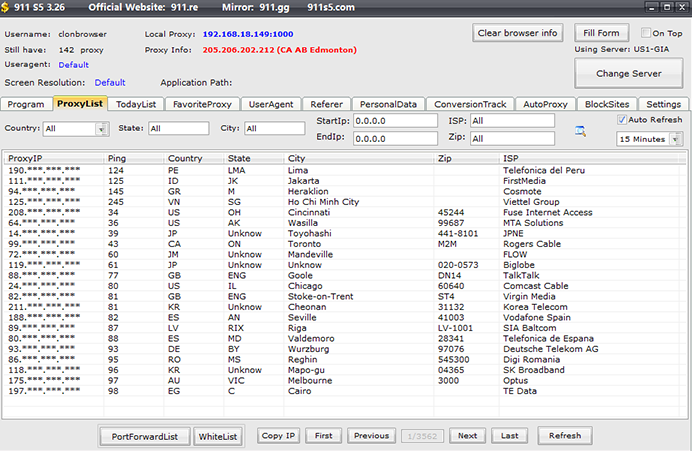

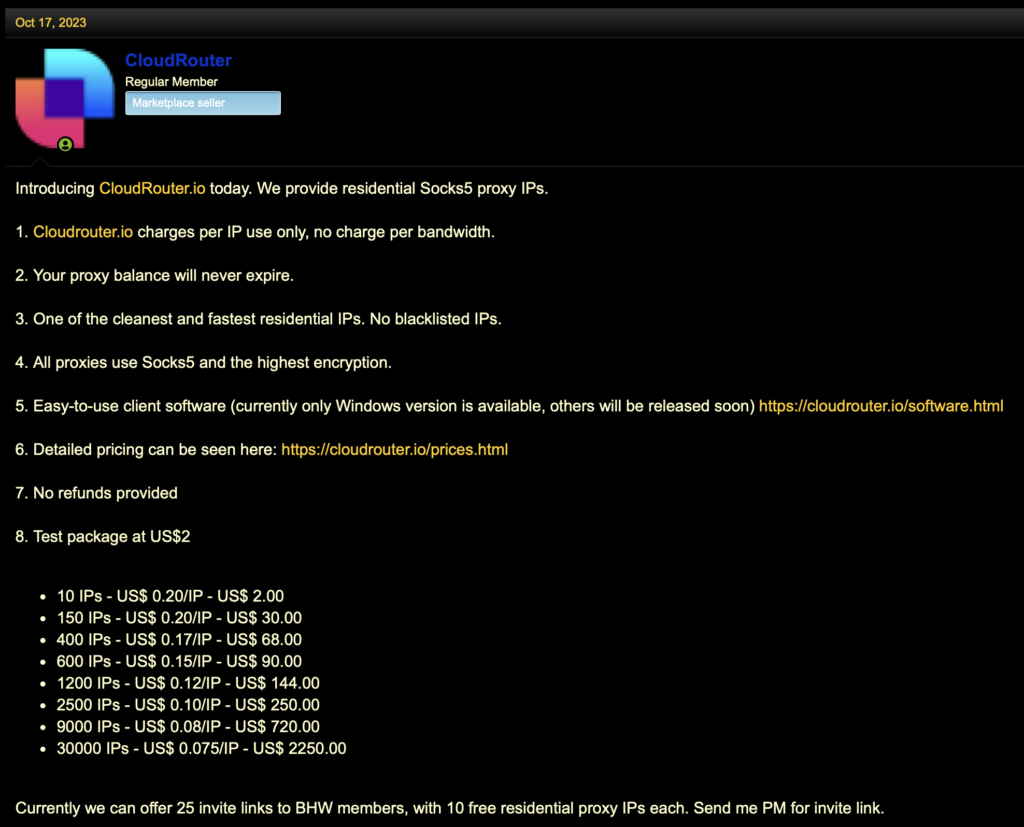

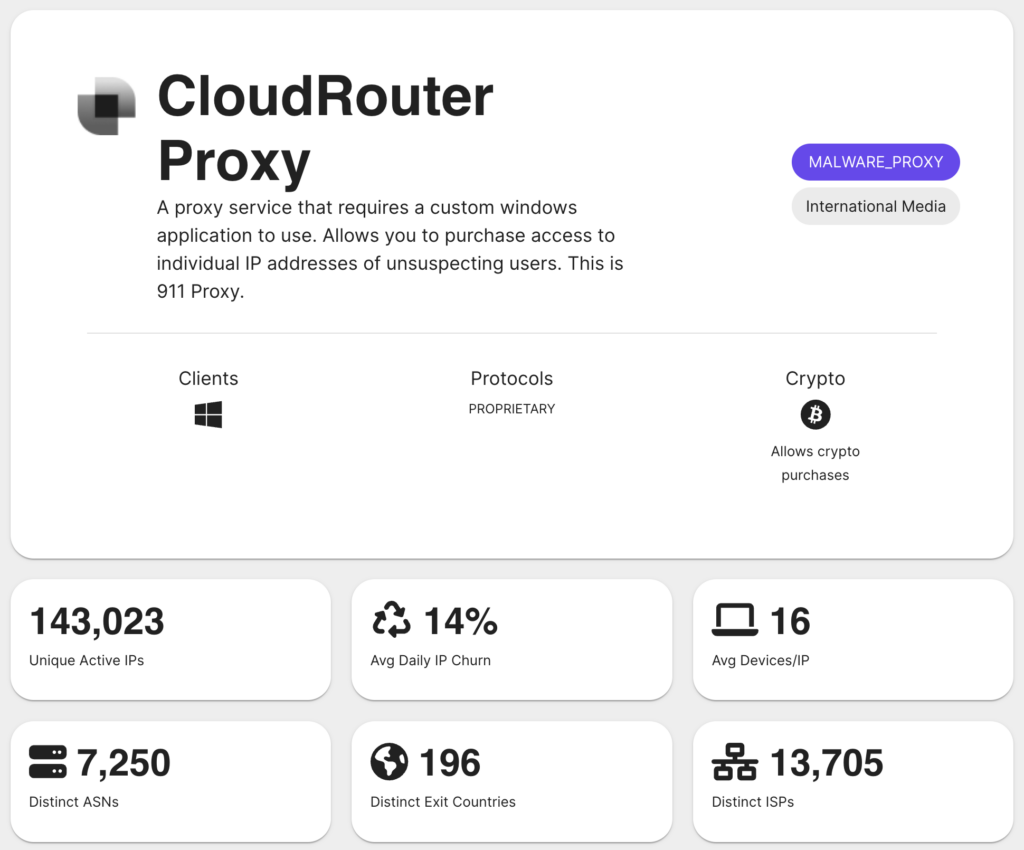

An interesting candidate to actually fill 911’s shoes recently popped up on our radar: a residential proxy service known as CloudRouter that markets itself as having “high-quality” residential IPs that users can buy on a per-IP basis using a native Windows client. This was the modus operandi of 911.re. Our interest was immediately piqued, as residential proxy services tend to all look the same (web interface, rotating or static sessions, pay per gigabyte, etc). This one looked markedly different and yet familiar.

Upon downloading and executing the client, the similarity was unmistakable. Following a hunch, we checked out the network requests and sure enough, nothing had changed; all the API paths were identical. 911’s back, baby, Voldemort-style. The legendary criminal proxy service has found its footing once again and resumed operations under a new name. Only one question remains: what app or apps are supplying the IPs for this new incarnation?

A rose by any other name

If the operators of 911 were lazy enough to reuse the same interface and backend (and I guess who can blame them), it’s a safe bet that whatever app or apps are supplying their IPs are equally as obvious.

In the past, a key giveaway has been the verbiage in the free VPN apps marketing and/or EULA; these are usually just copy and pasted between all the clones. So that’s probably a good place to start. Can we Google some phrases from MaskVPN’s EULA and find anything obvious?

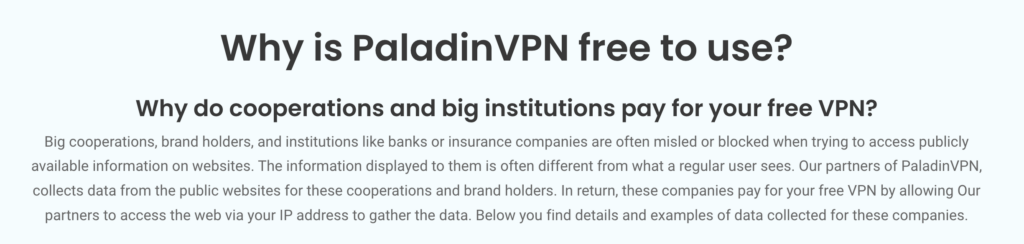

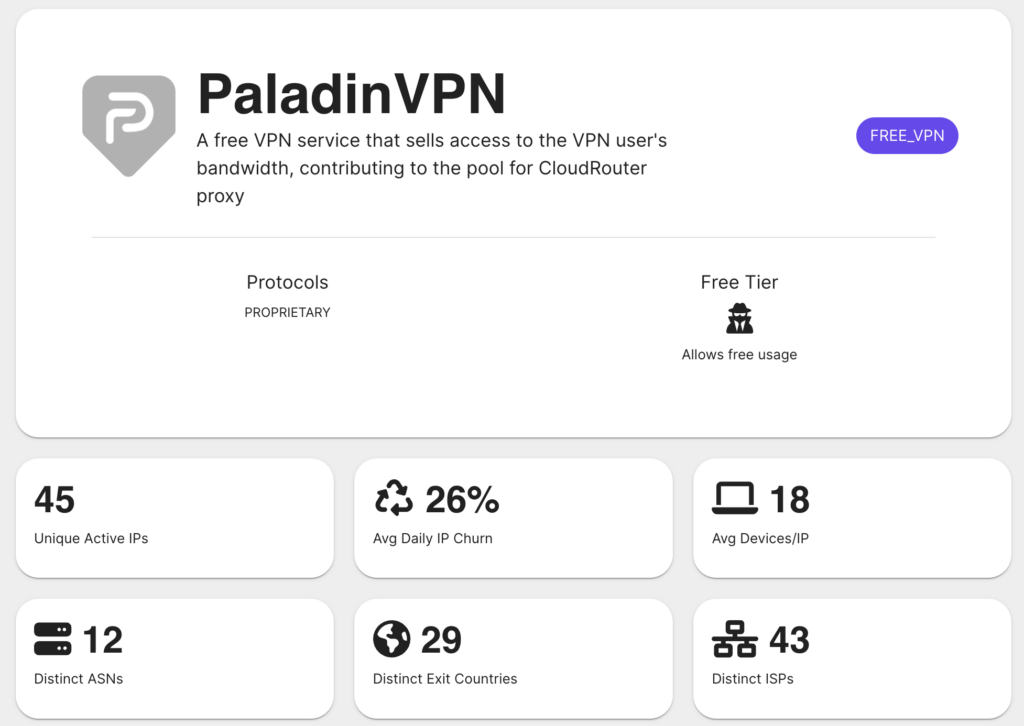

Well that was easy. PaladinVPN is a “Free VPN” app, allowing users to route their traffic from their choice of 44(!) datacenter exits all over the world with no registration or payment required. But like the curling of a monkey’s paw, there’s always a catch.

I guess I have to give PaladinVPN some credit for, at the very least, warning their users that their IP is about to be co-opted by “companies” and “partners”. In any event, this a pretty good suspect in our search for the app that is (at least partially) feeding the IP pool for CloudRouter.

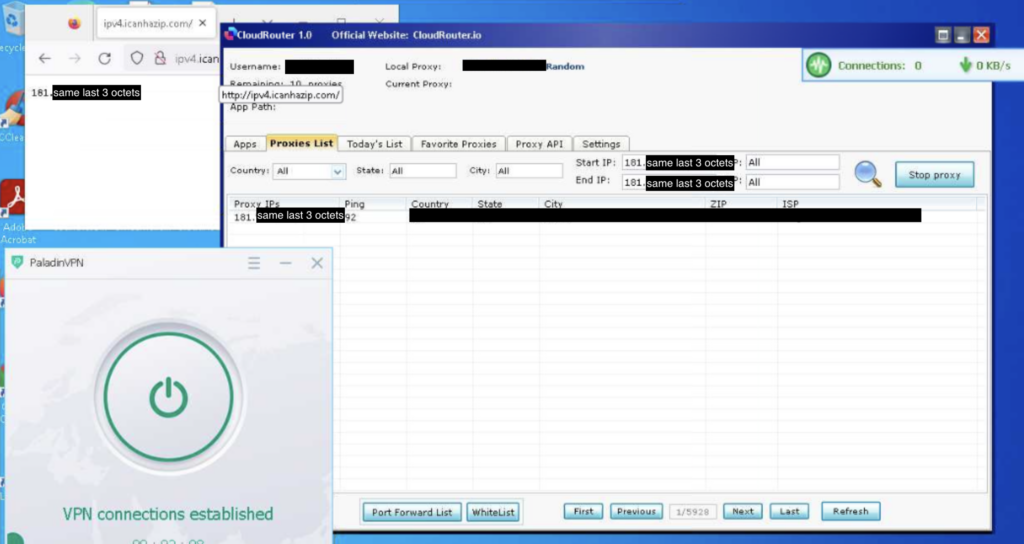

As it turns out, the easiest way to test this theory was to download and run PaladinVPN and see if we can buy our own IP on CloudRouter’s interface.

And there it is. Upon firing up PaladinVPN, you are nearly immediately added to the list of purchasable IPs in CloudRouter’s interface. Our hunt was over as quickly as it started.

The lazy lie

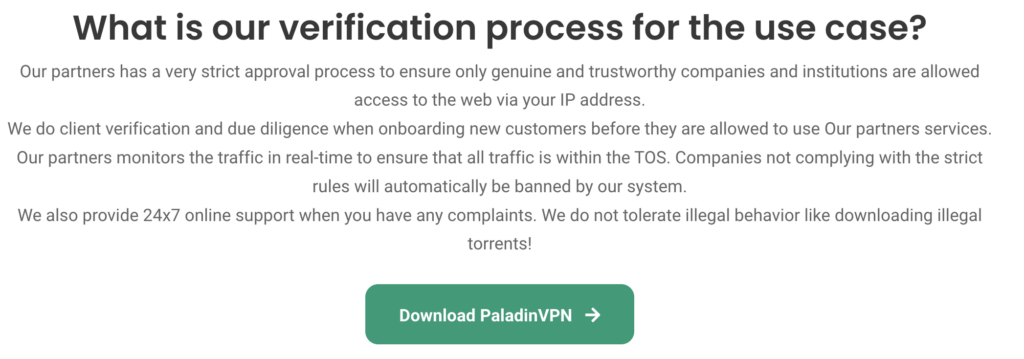

Let’s read Paladin’s marketing a bit further. Maybe they elaborate on the shadowy entities who are about to use your IP address for who knows what.

Some key phrases from their supposed KYC: “strict approval process”, “genuine and trustworthy companies and institutions”, “client verification and due diligence”.

Turns out their “strict approval process” ends at any script kiddie on BlackHatWorld with access to $2 in Bitcoin.

Slaying the Hydra

We’d be remiss if we didn’t mention the IOCs for CloudRouter. The C2 servers are located at the IP addresses below; you’d see callouts on TCP port 500 to them from “compromised” devices.

98.126.169.2 67.229.56.2 67.198.222.194 67.198.221.50 67.198.221.250 67.198.221.226 67.198.221.194 67.198.221.186 67.198.212.2 174.139.10.82

At time of writing, we track all 44 PaladinVPN exit IPs and some ~140,000 CloudRouter IPs. It seems unlikely that the entirety of CloudRouter’s pool is stemming from a single terrible free VPN application; we’re not entirely sure where the rest are coming from. Frankly, of the ~22,000,000 residential proxy IPs we track, we likely couldn’t give a concrete source for 80% of them. This is the true insidiousness of the residential proxy. They are ubiquitous, they are stealthy, and they are under-appreciated for the extreme risk of fraud and abuse they present.

Monitoring malicious proxies such as 911.re and CloudRouter is an unending challenge. The lucrative nature of the residential proxy market ensures that as soon as one service goes dark, another inevitably takes its place, like The Hydra growing another head. Check out our Community Dashboard to get some insight into our extensive efforts in tracking these services.