Residential proxy sourcing: witting vs. unwitting

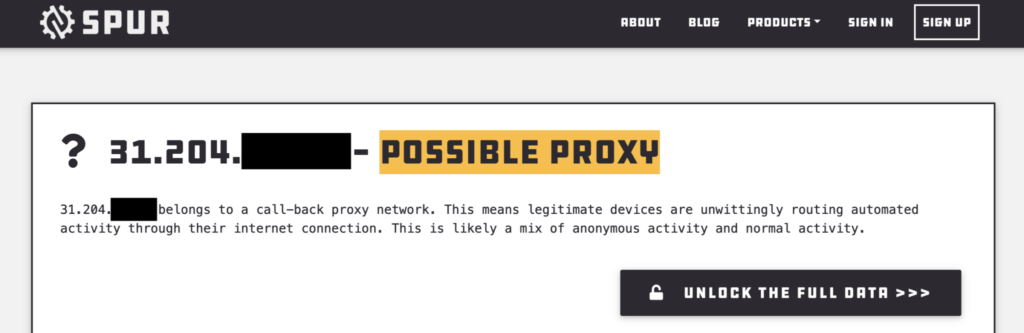

Residential proxies – normal user devices (such as phones and PCs) with proxy software installed – present a tricky challenge to online services combating fraud and abuse. Access to these proxies is sold by commercial proxy services, allowing paying customers to co-opt the Internet connection of otherwise benign users all over the world.

While conventional datacenter-hosted proxies are relatively static and therefore easily catalogued and blocked, residential proxies are far more ethereal. Proxied Internet traffic passing through residential proxies looks real in the sense that it is indeed coming from common user devices, oftentimes blending in with normal traffic. Moreover, each web request from a user routing their traffic through a residential proxy service can appear to be originating from a new location on the other side of the globe. It is these insidious advantages over their datacenter counterparts that make residential proxies so much more appealing to customers of proxy services.

There is a massive market for clean (read: not on blocklist) IP addresses from residential IP space, with proxy providers collectively touting hundreds of millions of endpoints. The provenance of these proxies can be lumped into two main categories: witting and unwitting installers of the proxy software. In other words, is the user who owns the “clean IP address” aware that they’ve installed and are allowing the free use of their bandwidth and IP reputation?

The “Good”

Falling under the witting category, there are several residential proxy providers that claim to source their clean IP addresses in an “ethical” manner – though for more than a few of these services, “ethical” simply means “not malware”.

The siren’s call of passive income

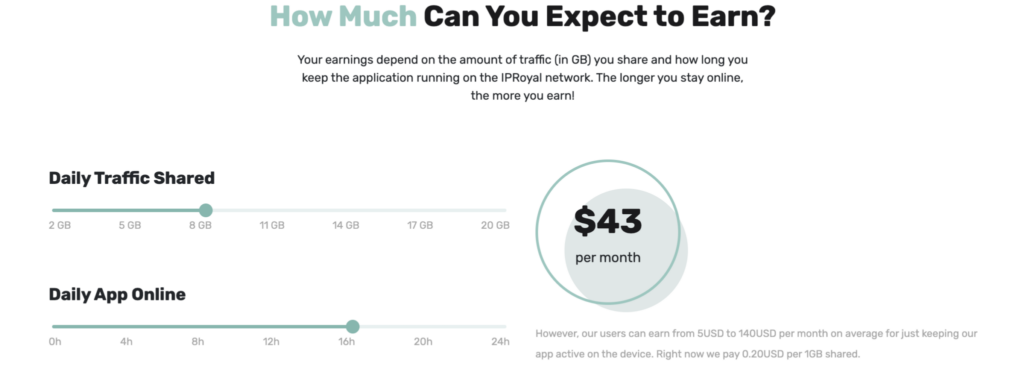

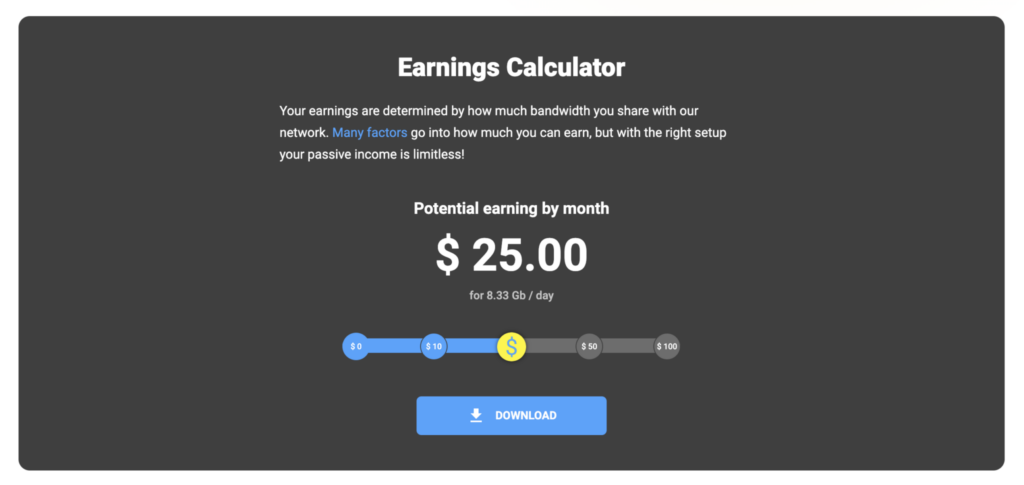

If you’re looking to transmute your bandwidth into beer money, there are a handful of residential proxy providers who claim to source their IP address pool from witting and incentivized users, generally by means of an app that is installed on your phone or PC. A few examples are IPRoyal and Rayobyte (formerly Blazing SEO). Standard practice is to perform runtime checks to ensure the participating device is coming from registered residential IP space (i.e.: Internet service providers like Comcast), as opposed to datacenters.

IProyal’s aptly-named Pawns app has support for Windows, Mac, Linux, and Android.

Rayobyte’s equivalent is an Android app called Cash Raven, with promises of support for Windows by late 2022.

It seems like easy money but – like all things that seem too good to be true – caveat emptor/venditor applies. There are risks involved with participating in these networks (that term used loosely here; they could also be classified as botnets). The consumers of these proxies can direct their Internet traffic through your device, which can range the spectrum from boring web scraping en masse to far more morally dubious and potentially illegal activities like cyber stalking, harassment, hacking, and consumption and distribution of CSAM. That is a lot of risk for $25 a month.

In these scenarios, a likely outcome may be your IP being added to a blocklist, and consequently, loss of access to certain services and web applications. A much worse outcome could be a very unpleasant knock on your door from men in suits.

The Bad

Apps promising passive income is the extent of what we could call “ethical” in the world of proxy procurement. The next set of proxy services we can confidently label unwitting unless you enjoy reading the Terms of Service of every piece of software you use.

There’s no such thing as a free lunch

Have you ever heard the axiom, “if you’re not paying for a service, you’re the product”? For seasoned denizens of the web, this cliche is the Golden Rule of the Internet.

As we’ve touched on in the blog post linked above, the majority source of residential proxies are monetization SDKs. In addition to ad revenue, a popular vector for making money off your free app is selling your users to proxy providers. By means of the inclusion of a simple SDK to the app’s source code and (if we’re lucky) a small amendment to the app’s Terms of Service, suddenly that free puzzle game you downloaded is allowing propagandists in Russia to tweet fake news from your home IP address in Kokomo, Indiana.

One such example of a popular residential proxy provider is Proxyrack, which offers an Android SDK to the developers of free apps to monetize their applications without using advertisements.

In some cases, this scenario presents itself shrouded in irony: by installing a “free VPN” app and seeking to protect your Internet activity from prying eyes, you open yourself up to free-use of your connection by proxy services offering the same assurance of privacy and anonymity. For example, the now defunct free VPN app Mask VPN allowed users to change their IP address and anonymize their Internet activity free of cost, with the caveat via an addition to the Terms of Service indicating that by using the app, you agree to allow your device to be a peer in the criminal proxy service 911.re.

RIP 911.re and, by proxy (pun intended), Mask VPN.

As a general rule, it’s important to internalize that your device is a means to run code. At the end of the day, anything you install on your favorite gateway to the Internet is capable of accessing, manipulating, and exploiting that device. In practice, this is often as benign as serving you ads, but you should approach every piece of 3rd party software running on your machine as a potential threat vector to your privacy and, in this case, your IP reputation. Be extra weary of free applications; understand exactly with what you are truly paying.

The Ugly

Undoubtedly unwitting. Outright malware, these proxies are sourced from compromised PCs and SOHO routers. Example networks include Luxsocks, Faceless, and Socksescort.

Proxy zombie army

These proxies are a monetization vector for botnet operators. The host devices have been pwned and are now operating at the whims of the malware controllers. Botnets have historically been rented out to perform denial-of-service attacks or to send spam, but more recently another easy method of monetization has been to sell access (via a web or desktop application) to proxy software running on the compromised devices.

Typically, these proxy networks are harder to enumerate and block, and are therefore more expensive per-endpoint to the proxy customer. Whereas other residential proxies allow default access to a large subset or the totality of their IP pool on a randomized basis, these malware proxy networks charge customers per-IP and allow fine-grained access by desired geolocation down to the city-level.

The operators of these malware proxies are incentivized to reduce usage of their bots in an effort to fly under the radar, which – in addition to the risk associated with operating these illegal networks – is why they can charge a premium for their services. Still, you especially don’t want the customers of these services routing their traffic through your home or office. Nothing good comes from these proxies.

Overwhelmed? We can help

The sourcing of residential proxies spans the spectrum between legitimate and illegitimate, and tracking them can be a Sisyphean effort for those fighting fraud and abuse on the Internet.

Spur tracks residential proxies (along with datacenter proxies and VPNs) so you don’t have to! Use our free tool ipctx.me to immediately determine if we’ve detected your IP address among anonymizing infrastructure. If you’re an online service that suffers from abuse from seemingly innocuous IPs, Spur’s context dashboard, API, and data feed products can help expose malicious traffic from co-opted residential sources.